FreeRTOS (pronounced "free-arr-toss") is an open source real-time operating system (RTOS) for embedded systems. FreeRTOS supports many different architectures and compiler toolchains, and is designed to be "small, simple, and easy to use".

FreeRTOS is under active development, and has been since Richard Barry started work on it in 2002. As for me, I'm not a developer of or contributor to FreeRTOS, I'm merely a user and a fan. As a result, this chapter will favor the "what" and "how" of FreeRTOS's architecture, with less of the "why" than other chapters in this book.

Like all operating systems, FreeRTOS's main job is to run tasks. Most of FreeRTOS's code involves prioritizing, scheduling, and running user-defined tasks. Unlike all operating systems, FreeRTOS is a real-time operating system which runs on embedded systems.

By the end of this chapter I hope that you'll understand the basic architecture of FreeRTOS. Most of FreeRTOS is dedicated to running tasks, so you'll get a good look at exactly how FreeRTOS does that.

If this is your first look under the hood of an operating system, I also hope that you'll learn the basics about how any OS works. FreeRTOS is relatively simple, especially when compared to Windows, Linux, or OS X, but all operating systems share the same basic concepts and goals, so looking at any OS can be instructive and interesting.

"Embedded" and "real-time" can mean different things to different people, so let's define them as FreeRTOS uses them.

An embedded system is a computer system that is designed to do only a few things, like the system in a TV remote control, in-car GPS, digital watch, or pacemaker. Embedded systems are typically smaller and slower than general purpose computer systems, and are also usually less expensive. A typical low-end embedded system may have an 8-bit CPU running at 25MHz, a few KB of RAM, and maybe 32KB of flash memory. A higher-end embedded system may have a 32-bit CPU running at 750MHz, a GB of RAM, and multiple GB of flash memory.

Real-time systems are designed to do something within a certain amount of time; they guarantee that stuff happens when it's supposed to.

A pacemaker is an excellent example of a real-time embedded system. A pacemaker must contract the heart muscle at the right time to keep you alive; it can't be too busy to respond in time. Pacemakers and other real-time embedded systems are carefully designed to run their tasks on time, every time.

FreeRTOS is a relatively small application. The minimum core of

FreeRTOS is only three source (.c) files and a handful of

header files, totalling just under 9000 lines of code, including

comments and blank lines. A typical binary code image is less than

10KB.

FreeRTOS's code breaks down into three main areas: tasks, communication, and hardware interfacing.

tasks.c and task.h do all the heavy lifting for

creating, scheduling, and maintaining tasks.

queue.c and queue.h handle FreeRTOS

communication. Tasks and interrupts use queues to send data to each

other and to signal the use of critical resources using semaphores

and mutexes.

The hardware-independent FreeRTOS layer sits on top of a hardware-dependent layer. This hardware-dependent layer knows how to talk to whatever chip architecture you choose. Figure 3.1 shows FreeRTOS's layers.

FreeRTOS ships with all the hardware-independent as well as hardware-dependent code you'll need to get a system up and running. It supports many compilers (CodeWarrior, GCC, IAR, etc.) as well as many processor architectures (ARM7, ARM Cortex-M3, various PICs, Silicon Labs 8051, x86, etc.). See the FreeRTOS website for a list of supported architectures and compilers.

FreeRTOS is highly configurable by design. FreeRTOS can be built as a single CPU, bare-bones RTOS, supporting only a few tasks, or it can be built as a highly functional multicore beast with TCP/IP, a file system, and USB.

Configuration options are selected in FreeRTOSConfig.h by

setting various #defines. Clock speed, heap size, mutexes, and

API subsets are all configurable in this file, along with many other

options. Here are a few examples that set the maximum number of task

priority levels, the CPU frequency, the system tick frequency, the

minimal stack size and the total heap size:

#define configMAX_PRIORITIES ( ( unsigned portBASE_TYPE ) 5 ) #define configCPU_CLOCK_HZ ( 12000000UL ) #define configTICK_RATE_HZ ( ( portTickType ) 1000 ) #define configMINIMAL_STACK_SIZE ( ( unsigned short ) 100 ) #define configTOTAL_HEAP_SIZE ( ( size_t ) ( 4 * 1024 ) )

Hardware-dependent code lives in separate files for each compiler

toolchain and CPU architecture. For example, if you're working with

the IAR compiler on an ARM Cortex-M3 chip, the hardware-dependent code

lives in the FreeRTOS/Source/portable/IAR/ARM_CM3/ directory.

portmacro.h declares all of the hardware-specific functions,

while port.c and portasm.s contain all of the actual

hardware-dependent code. The hardware-independent header file

portable.h #include's the correct portmacro.h

file at compile time. FreeRTOS calls the hardware-specific functions

using #define'd functions declared in portmacro.h.

Let's look at an example of how FreeRTOS calls a hardware-dependent

function. The hardware-independent file tasks.c frequently

needs to enter a critical section of code to prevent

preemption. Entering a critical section happens differently on

different architectures, and the hardware-independent tasks.c

does not want to have to understand the hardware-dependent details.

So tasks.c calls the global macro

portENTER_CRITICAL(), glad to be ignorant of how it actually

works. Assuming we're using the IAR compiler on an ARM Cortex-M3

chip, FreeRTOS is built with the file

FreeRTOS/Source/portable/IAR/ARM_CM3/portmacro.h which defines

portENTER_CRITICAL() like this:

#define portENTER_CRITICAL() vPortEnterCritical()

vPortEnterCritical() is actually defined in

FreeRTOS/Source/portable/IAR/ARM_CM3/port.c. The port.c

file is hardware-dependent, and contains code that understands the IAR

compiler and the Cortex-M3 chip. vPortEnterCritical() enters

the critical section using this hardware-specific knowledge and

returns to the hardware-independent tasks.c.

The portmacro.h file also defines an architecture's basic data

types. Data types for basic integer variables, pointers, and the

system timer tick data type are defined like this for the IAR compiler

on ARM Cortex-M3 chips:

#define portBASE_TYPE long // Basic integer variable type #define portSTACK_TYPE unsigned long // Pointers to memory locations typedef unsigned portLONG portTickType; // The system timer tick type

This method of using data types and functions through thin layers of

#defines may seem a bit complicated, but it allows FreeRTOS to

be recompiled for a completely different system architecture by

changing only the hardware-dependent files. And if you want to run

FreeRTOS on an architecture it doesn't currently support, you only have

to implement the hardware-dependent functionality which is much

smaller than the hardware-independent part of FreeRTOS.

As we've seen, FreeRTOS implements hardware-dependent functionality

with C preprocessor #define macros. FreeRTOS also uses

#define for plenty of hardware-independent code. For

non-embedded applications this frequent use of #define is a

cardinal sin, but in many smaller embedded systems the overhead for

calling a function is not worth the advantages that "real" functions

offer.

Each task has a user-assigned priority between 0 (the lowest priority)

and the compile-time value of configMAX_PRIORITIES-1 (the

highest priority). For instance, if configMAX_PRIORITIES is

set to 5, then FreeRTOS will use 5 priority levels: 0 (lowest

priority), 1, 2, 3, and 4 (highest priority).

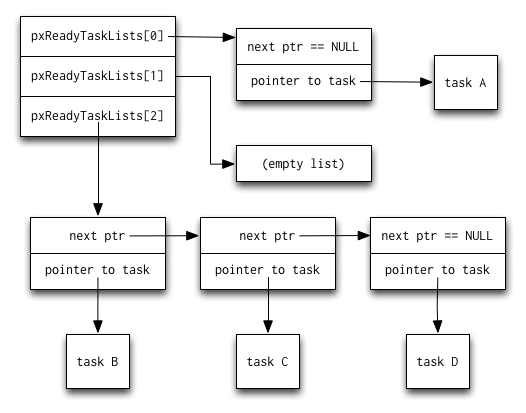

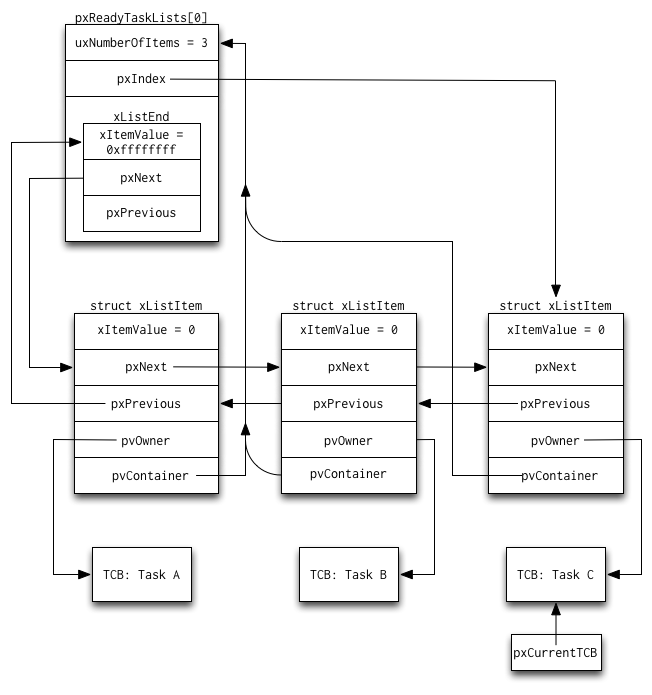

FreeRTOS uses a "ready list" to keep track of all tasks that are currently ready to run. It implements the ready list as an array of task lists like this:

static xList pxReadyTasksLists[ configMAX_PRIORITIES ]; /* Prioritised ready tasks. */

pxReadyTasksLists[0] is a list of all ready priority 0 tasks,

pxReadyTasksLists[1] is a list of all ready priority 1 tasks,

and so on, all the way up to

pxReadyTasksLists[configMAX_PRIORITIES-1].

The heartbeat of a FreeRTOS system is called the system tick. FreeRTOS

configures the system to generate a periodic tick interrupt. The user

can configure the tick interrupt frequency, which is typically in the

millisecond range. Every time the tick interrupt fires, the

vTaskSwitchContext() function is called.

vTaskSwitchContext() selects the highest-priority ready task

and puts it in the pxCurrentTCB variable like this:

/* Find the highest-priority queue that contains ready tasks. */

while( listLIST_IS_EMPTY( &( pxReadyTasksLists[ uxTopReadyPriority ] ) ) )

{

configASSERT( uxTopReadyPriority );

--uxTopReadyPriority;

}

/* listGET_OWNER_OF_NEXT_ENTRY walks through the list, so the tasks of the same

priority get an equal share of the processor time. */

listGET_OWNER_OF_NEXT_ENTRY( pxCurrentTCB, &( pxReadyTasksLists[ uxTopReadyPriority ] ) );

Before the while loop starts, uxTopReadyPriority is guaranteed

to be greater than or equal to the priority of the highest-priority

ready task. The while() loop starts at priority level

uxTopReadyPriority and walks down through the

pxReadyTasksLists[] array to find the highest-priority level

with ready tasks. listGET_OWNER_OF_NEXT_ENTRY() then grabs

the next ready task from that priority level's ready list.

Now pxCurrentTCB points to the highest-priority task, and when

vTaskSwitchContext() returns the hardware-dependent code starts

running that task.

Those nine lines of code are the absolute heart of FreeRTOS. The other 8900+ lines of FreeRTOS are there to make sure those nine lines are all that's needed to keep the highest-priority task running.

Figure 3.2 is a high-level picture of what a ready list looks like. This example has three priority levels, with one priority 0 task, no priority 1 tasks, and three priority 2 tasks. This picture is accurate but not complete; it's missing a few details which we'll fill in later.

Now that we have the high-level overview out of the way, let's dive in to the details. We'll look at the three main FreeRTOS data structures: tasks, lists, and queues.

The main job of all operating systems is to run and coordinate user tasks. Like many operating systems, the basic unit of work in FreeRTOS is the task. FreeRTOS uses a Task Control Block (TCB) to represent each task.

The TCB is defined in tasks.c like this:

typedef struct tskTaskControlBlock

{

volatile portSTACK_TYPE *pxTopOfStack; /* Points to the location of

the last item placed on

the tasks stack. THIS

MUST BE THE FIRST MEMBER

OF THE STRUCT. */

xListItem xGenericListItem; /* List item used to place

the TCB in ready and

blocked queues. */

xListItem xEventListItem; /* List item used to place

the TCB in event lists.*/

unsigned portBASE_TYPE uxPriority; /* The priority of the task

where 0 is the lowest

priority. */

portSTACK_TYPE *pxStack; /* Points to the start of

the stack. */

signed char pcTaskName[ configMAX_TASK_NAME_LEN ]; /* Descriptive name given

to the task when created.

Facilitates debugging

only. */

#if ( portSTACK_GROWTH > 0 )

portSTACK_TYPE *pxEndOfStack; /* Used for stack overflow

checking on architectures

where the stack grows up

from low memory. */

#endif

#if ( configUSE_MUTEXES == 1 )

unsigned portBASE_TYPE uxBasePriority; /* The priority last

assigned to the task -

used by the priority

inheritance mechanism. */

#endif

} tskTCB;

The TCB stores the address of the stack start address in

pxStack and the current top of stack in pxTopOfStack. It

also stores a pointer to the end of the stack in pxEndOfStack

to check for stack overflow if the stack grows "up" to higher

addresses. If the stack grows "down" to lower addresses then stack

overflow is checked by comparing the current top of stack against the

start of stack memory in pxStack.

The TCB stores the initial priority of the task in uxPriority

and uxBasePriority. A task is given a priority when it is

created, and a task's priority can be changed. If FreeRTOS

implements priority inheritance then it uses uxBasePriority to

remember the original priority while the task is temporarily elevated

to the "inherited" priority. (See the discussion about mutexes below

for more on priority inheritance.)

Each task has two list items for use in FreeRTOS's various scheduling

lists. When a task is inserted into a list FreeRTOS doesn't insert a

pointer directly to the TCB. Instead, it inserts a pointer to either

the TCB's xGenericListItem or xEventListItem. These

xListItem variables let the FreeRTOS lists be smarter than if

they merely held a pointer to the TCB. We'll see an example of this

when we discuss lists later.

A task can be in one of four states: running, ready to run, suspended, or blocked. You might expect each task to have a variable that tells FreeRTOS what state it's in, but it doesn't. Instead, FreeRTOS tracks task state implicitly by putting tasks in the appropriate list: ready list, suspended list, etc. The presence of a task in a particular list indicates the task's state. As a task changes from one state to another, FreeRTOS simply moves it from one list to another.

We've already touched on how a task is selected and scheduled with the

pxReadyTasksLists array; now let's look at how a task is

initially created. A task is created when the xTaskCreate()

function is called. FreeRTOS uses a newly allocated TCB object to

store the name, priority, and other details for a task, then allocates

the amount of stack the user requests (assuming there's enough memory

available) and remembers the start of the stack memory in TCB's

pxStack member.

The stack is initialized to look as if the new task is already running and was interrupted by a context switch. This way the scheduler can treat newly created tasks exactly the same way as it treats tasks that have been running for a while; the scheduler doesn't need any special case code for handling new tasks.

The way that a task's stack is made to look like it was interrupted by a context switch depends on the architecture FreeRTOS is running on, but this ARM Cortex-M3 processor's implementation is a good example:

unsigned int *pxPortInitialiseStack( unsigned int *pxTopOfStack,

pdTASK_CODE pxCode,

void *pvParameters )

{

/* Simulate the stack frame as it would be created by a context switch interrupt. */

pxTopOfStack--; /* Offset added to account for the way the MCU uses the stack on

entry/exit of interrupts. */

*pxTopOfStack = portINITIAL_XPSR; /* xPSR */

pxTopOfStack--;

*pxTopOfStack = ( portSTACK_TYPE ) pxCode; /* PC */

pxTopOfStack--;

*pxTopOfStack = 0; /* LR */

pxTopOfStack -= 5; /* R12, R3, R2 and R1. */

*pxTopOfStack = ( portSTACK_TYPE ) pvParameters; /* R0 */

pxTopOfStack -= 8; /* R11, R10, R9, R8, R7, R6, R5 and R4. */

return pxTopOfStack;

}

The ARM Cortex-M3 processor pushes registers on the stack when a task

is interrupted. pxPortInitialiseStack() modifies the stack to

look like the registers were pushed even though the task hasn't

actually started running yet. Known values are stored to the stack

for the ARM registers xPSR, PC, LR, and R0. The

remaining registers R1 -- R12 get stack space allocated for them

by decrementing the top of stack pointer, but no specific data is

stored in the stack for those registers. The ARM architecture says

that those registers are undefined at reset, so a (non-buggy) program

will not rely on a known value.

After the stack is prepared, the task is almost ready to run. First though, FreeRTOS disables interrupts: We're about to start mucking with the ready lists and other scheduler structures and we don't want anyone else changing them underneath us.

If this is the first task to ever be created, FreeRTOS initializes the

scheduler's task lists. FreeRTOS's scheduler has an array of ready

lists, pxReadyTasksLists[], which has one ready list for each

possible priority level. FreeRTOS also has a few other lists for

tracking tasks that have been suspended, killed, and delayed. These

are all initialized now as well.

After any first-time initialization is done, the new task is added to the ready list at its specified priority level. Interrupts are re-enabled and new task creation is complete.

After tasks, the most used FreeRTOS data structure is the list. FreeRTOS uses its list structure to keep track of tasks for scheduling, and also to implement queues.

The FreeRTOS list is a standard circular doubly linked list with a couple of interesting additions. Here's a list element:

struct xLIST_ITEM

{

portTickType xItemValue; /* The value being listed. In most cases

this is used to sort the list in

descending order. */

volatile struct xLIST_ITEM * pxNext; /* Pointer to the next xListItem in the

list. */

volatile struct xLIST_ITEM * pxPrevious; /* Pointer to the previous xListItem in

the list. */

void * pvOwner; /* Pointer to the object (normally a TCB)

that contains the list item. There is

therefore a two-way link between the

object containing the list item and

the list item itself. */

void * pvContainer; /* Pointer to the list in which this list

item is placed (if any). */

};

Each list element holds a number, xItemValue, that is the

usually the priority of the task being tracked or a timer value for

event scheduling. Lists are kept in high-to-low priority order,

meaning that the highest-priority xItemValue (the largest number) is

at the front of the list and the lowest priority xItemValue (the

smallest number) is at the end of the list.

The pxNext and pxPrevious pointers are standard linked

list pointers. pvOwner is a pointer to the owner of the list element. This is

usually a pointer to a task's TCB object. pvOwner is used to

make task switching fast in vTaskSwitchContext(): once the

highest-priority task's list element is found in

pxReadyTasksLists[], that list element's pvOwner pointer

leads us directly to the TCB needed to schedule the task.

pvContainer points to the list that this item is in. It is used

to quickly determine if a list item is in a particular list. Each

list element can be put in a list, which is defined as:

typedef struct xLIST

{

volatile unsigned portBASE_TYPE uxNumberOfItems;

volatile xListItem * pxIndex; /* Used to walk through the list. Points to

the last item returned by a call to

pvListGetOwnerOfNextEntry (). */

volatile xMiniListItem xListEnd; /* List item that contains the maximum

possible item value, meaning it is always

at the end of the list and is therefore

used as a marker. */

} xList;

The size of a list at any time is stored in uxNumberOfItems, for

fast list-size operations.

All new lists are initialized to contain a single element: the

xListEnd element. xListEnd.xItemValue is a sentinel

value which is equal to the largest value for the xItemValue

variable: 0xffff when portTickType is a 16-bit value and

0xffffffff when portTickType is a 32-bit value. Other list

elements may also have the same value; the insertion algorithm ensures

that xListEnd is always the last item in the list.

Since lists are sorted high-to-low, the xListEnd element is

used as a marker for the start of the list. And since the list is

circular, this xListEnd element is also a marker for the end of

the list.

Most "traditional" list accesses you've used probably do all of their work within a single for() loop or function call like this:

for (listPtr = listStart; listPtr != NULL; listPtr = listPtr->next) {

// Do something with listPtr here...

}

FreeRTOS frequently needs to access a list across multiple for() and

while() loops as well as function calls, and so it uses list functions

that manipulate the pxIndex pointer to walk the list. The list

function listGET_OWNER_OF_NEXT_ENTRY() does pxIndex =

pxIndex->pxNext; and returns pxIndex. (Of

course it does the proper end-of-list-wraparound detection too.) This

way the list itself is responsible for keeping track of "where you

are" while walking it using pxIndex, allowing the rest of

FreeRTOS to not worry about it.

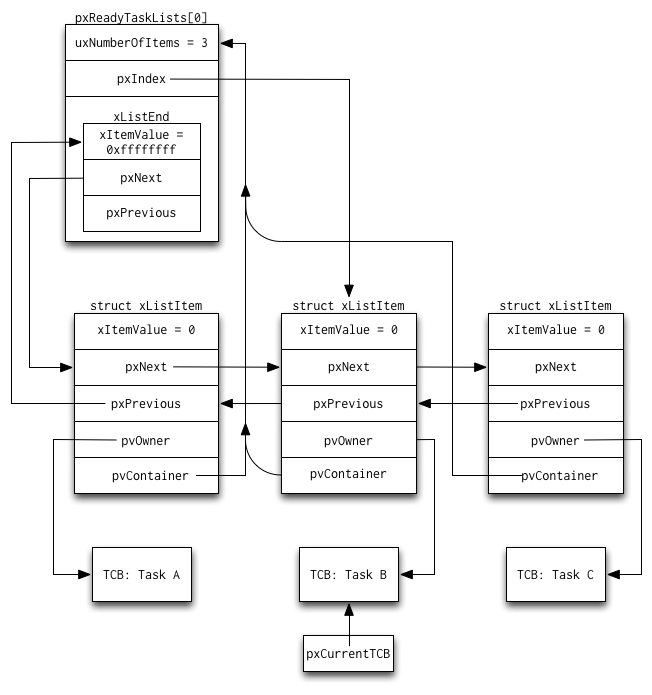

The pxReadyTasksLists[] list manipulation done in

vTaskSwitchContext() is a good example of how pxIndex is

used. Let's assume we have only one priority level, priority 0, and

there are three tasks at that priority level. This is similar to the

basic ready list picture we looked at earlier, but this time we'll

include all of the data structures and fields.

As you can see in Figure 3.3, pxCurrentTCB

indicates that we're currently running Task B. The next time

vTaskSwitchContext() runs, it calls

listGET_OWNER_OF_NEXT_ENTRY() to get the next task to

run. This function uses pxIndex->pxNext to figure

out the next task is Task C, and now pxIndex points to Task C's

list element and pxCurrentTCB points to Task C's TCB, as shown in

Figure 3.4.

Note that each struct xListItem object is actually the

xGenericListItem object from the associated TCB.

FreeRTOS allows tasks to communicate and synchronize with each other using queues. Interrupt service routines (ISRs) also use queues for communication and synchronization.

The basic queue data structure is:

typedef struct QueueDefinition

{

signed char *pcHead; /* Points to the beginning of the queue

storage area. */

signed char *pcTail; /* Points to the byte at the end of the

queue storage area. One more byte is

allocated than necessary to store the

queue items; this is used as a marker. */

signed char *pcWriteTo; /* Points to the free next place in the

storage area. */

signed char *pcReadFrom; /* Points to the last place that a queued

item was read from. */

xList xTasksWaitingToSend; /* List of tasks that are blocked waiting

to post onto this queue. Stored in

priority order. */

xList xTasksWaitingToReceive; /* List of tasks that are blocked waiting

to read from this queue. Stored in

priority order. */

volatile unsigned portBASE_TYPE uxMessagesWaiting; /* The number of items currently

in the queue. */

unsigned portBASE_TYPE uxLength; /* The length of the queue

defined as the number of

items it will hold, not the

number of bytes. */

unsigned portBASE_TYPE uxItemSize; /* The size of each items that

the queue will hold. */

} xQUEUE;

This is a fairly standard queue with head and tail pointers, as well as pointers to keep track of where we've just read from and written to.

When creating a queue, the user specifies the length of the queue and

the size of each item to be tracked by the queue. pcHead and

pcTail are used to keep track of the queue's internal

storage. Adding an item into a queue does a deep copy of the item into

the queue's internal storage.

FreeRTOS makes a deep copy instead of storing a pointer to the item because the lifetime of the item inserted may be much shorter than the lifetime of the queue. For instance, consider a queue of simple integers inserted and removed using local variables across several function calls. If the queue stored pointers to the integers' local variables, the pointers would be invalid as soon as the integers' local variables went out of scope and the local variables' memory was used for some new value.

The user chooses what to queue. The user can queue copies of items if the items are small, like in the simple integer example in the previous paragraph, or the user can queue pointers to the items if the items are large. Note that in both cases FreeRTOS does a deep copy: if the user chooses to queue copies of items then the queue stores a deep copy of each item; if the user chooses to queue pointers then the queue stores a deep copy of the pointer. Of course, if the user stores pointers in the queue then the user is responsible for managing the memory associated with the pointers. The queue doesn't care what data you're storing in it, it just needs to know the data's size.

FreeRTOS supports blocking and non-blocking queue insertions and removals. Non-blocking operations return immediately with a "Did the queue insertion work?" or "Did the queue removal work?" status. Blocking operations are specified with a timeout. A task can block indefinitely or for a limited amount of time.

A blocked task—call it Task A—will remain blocked as long as its insert/remove operation cannot complete and its timeout (if any) has not expired. If an interrupt or another task modifies the queue so that Task A's operation could complete, Task A will be unblocked. If Task A's queue operation is still possible by the time it actually runs then Task A will complete its queue operation and return "success". However, by the time Task A actually runs, it is possible that a higher-priority task or interrupt has performed yet another operation on the queue that prevents Task A from performing its operation. In this case Task A will check its timeout and either resume blocking if the timeout hasn't expired, or return with a queue operation "failed" status.

It's important to note that the rest of the system keeps going while a task is blocking on a queue; other tasks and interrupts continue to run. This way the blocked task doesn't waste CPU cycles that could be used productively by other tasks and interrupts.

FreeRTOS uses the xTasksWaitingToSend list to keep track of

tasks that are blocking on inserting into a queue. Each time an

element is removed from a queue the xTasksWaitingToSend list is

checked. If a task is waiting in that list the task is unblocked.

Similarly, xTasksWaitingToReceive keeps track of tasks that are

blocking on removing from a queue. Each time a new element is

inserted into a queue the xTasksWaitingToReceive list is

checked. If a task is waiting in that list the task is unblocked.

FreeRTOS uses its queues for communication between and within tasks. FreeRTOS also uses its queues to implement semaphores and mutexes.

Semaphores and mutexes may sound like the same thing, but they're not. FreeRTOS implements them similarly, but they're intended to be used in different ways. How should they be used differently? Embedded systems guru Michael Barr says it best in his article, "Mutexes and Semaphores Demystified":

The correct use of a semaphore is for signaling from one task to another. A mutex is meant to be taken and released, always in that order, by each task that uses the shared resource it protects. By contrast, tasks that use semaphores either signal ["send" in FreeRTOS terms] or wait ["receive" in FreeRTOS terms] - not both.

A mutex is used to protect a shared resource. A task acquires a mutex, uses the shared resource, then releases the mutex. No task can acquire a mutex while the mutex is being held by another task. This guarantees that only one task is allowed to use a shared resource at a time.

Semaphores are used by one task to signal another task. To quote Barr's article:

For example, Task 1 may contain code to post (i.e., signal or increment) a particular semaphore when the "power" button is pressed and Task 2, which wakes the display, pends on that same semaphore. In this scenario, one task is the producer of the event signal; the other the consumer.

If you're at all in doubt about semaphores and mutexes, please check out Michael's article.

FreeRTOS implements an N-element semaphore as a queue that can hold N

items. It doesn't store any actual data for the queue items; the

semaphore just cares how many queue entries are currently occupied,

which is tracked in the queue's uxMessagesWaiting field. It's

doing "pure synchronization", as the FreeRTOS header file

semphr.h calls it. Therefore the queue has a item size of zero

bytes (uxItemSize == 0). Each semaphore access increments or

decrements the uxMessagesWaiting field; no item or data copying

is needed.

Like a semaphore, a mutex is also implemented as a queue, but several

of the xQUEUE struct fields are overloaded using

#defines:

/* Effectively make a union out of the xQUEUE structure. */ #define uxQueueType pcHead #define pxMutexHolder pcTail

Since a mutex doesn't store any data in the queue, it doesn't need any

internal storage, and so the pcHead and pcTail fields

aren't needed. FreeRTOS sets the uxQueueType field (really the

pcHead field) to 0 to note that this queue is being used for a

mutex. FreeRTOS uses the overloaded pcTail fields to implement

priority inheritance for mutexes.

In case you're not familiar with priority inheritance, I'll quote Michael Barr again to define it, this time from his article, "Introduction to Priority Inversion":

[Priority inheritance] mandates that a lower-priority task inherit the priority of any higher-priority task pending on a resource they share. This priority change should take place as soon as the high-priority task begins to pend; it should end when the resource is released.

FreeRTOS implements priority inheritance using the

pxMutexHolder field (which is really just the

overloaded-by-#define pcTail field). FreeRTOS records

the task that holds a mutex in the pxMutexHolder field. When a

higher-priority task is found to be waiting on a mutex currently taken

by a lower-priority task, FreeRTOS "upgrades" the lower-priority

task to the priority of the higher-priority task until the mutex is

available again.

We've completed our look at the FreeRTOS architecture. Hopefully you now have a good feel for how FreeRTOS's tasks run and communicate. And if you've never looked at any OS's internals before, I hope you now have a basic idea of how they work.

Obviously this chapter did not cover all of FreeRTOS's architecture. Notably, I didn't mention memory allocation, ISRs, debugging, or MPU support. This chapter also did not discuss how to set up or use FreeRTOS. Richard Barry has written an excellent book, Using the FreeRTOS Real Time Kernel: A Practical Guide, which discusses exactly that; I highly recommend it if you're going to use FreeRTOS.

I would like to thank Richard Barry for creating and maintaining FreeRTOS, and for choosing to make it open source. Richard was very helpful in writing this chapter, providing some FreeRTOS history as well as a very valuable technical review.

Thanks also to Amy Brown and Greg Wilson for pulling this whole AOSA thing together.

Last and most (the opposite of "not least"), thanks to my wife Sarah for sharing me with the research and writing for this chapter. Luckily she knew I was a geek when she married me!